✢ Artifact Two ✢

𝄠 Some accompanying ambience 𝄠

Lamia (second version) with snakeskin on her lap by John William Waterhouse (1909)

Illustration from Carmilla by D. H. Friston (1872)

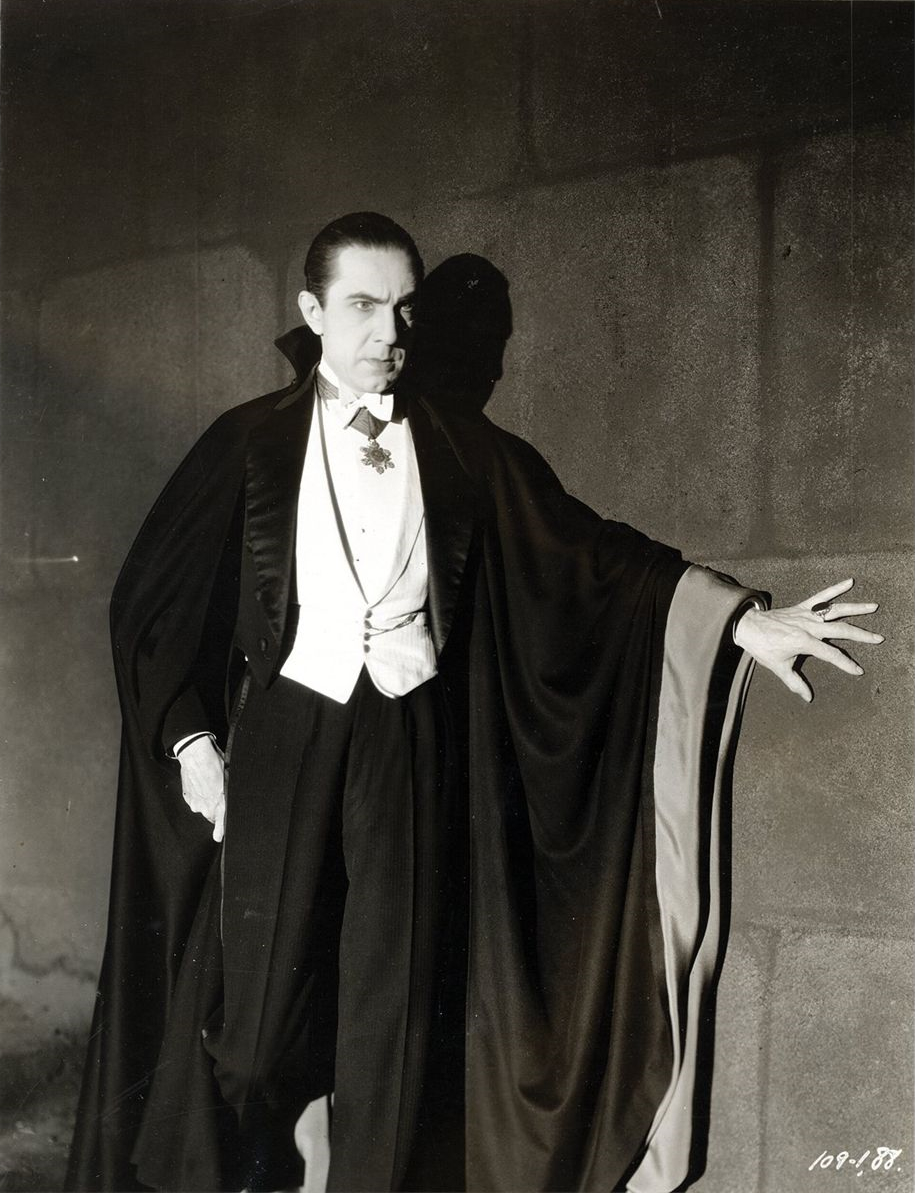

Bela Lugosi as Dracula in 1931's iconic Dracula

Since ancient times, there have been stories of malicious, blood-sucking creatures preying on humans. From the Greek Lamia to Mesopotamia's Lamashtu, these vampiric creatures have evolved into the modern

vampire, as primarily seen in eighteenth-century Europe. Ancient vampires were often born as such due to incestuous relationships or wedlock, but according to Montague Summers in Vampires and Vampirism, the European vampire was, one who has led a life of more than ordinary immorality and unbridled wickedness; a man of foul, gross and selfish passions, of evil ambitions, delighting in cruelty and blood

(77). As opposed to being born into misfortune, the eighteenth-century vampire made himself into one by inflicting misfortune upon others. Living a life steeped in sin made it easier for demons to claim one's corpse after death. In a largely Christian society that so desperately wished to reach Heaven in the afterlife, the notion of one's sins trapping them in the mortal realm for eternity was terrifying. Vampires leapt from legend to life, however, with accounts of individuals such as 1725's Peter Plogojowitz of Serbia. In Vampires, Burial, and Death: Folklore and Reality, Paul Barber explains that Plogojowitz, a rather unexceptional man, had returned from the dead and killed nine other villagers. When the authorities inspected his corpse, they found a body that barely looked dead with fresh blood in its mouth (6). Contemporaries were convinced that he had risen from the dead to drag the living down with him. Stories such as Peter Plogojowitz's brought vampires to the forefront of Europeans' anxiety during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Feeding off this fear, vampire media grew popular, largely starting with John William Polidori's 1819 publication, The Vampyre

. Ever since, they have stolen the spotlight and have arguably become the most represented monster

across all platforms of media. The vampire's renown can be largely attributed to the rhetoric of their tales and the ways their themes reflect contemporary fears.

A common motif in vampire stories is the notion of social isolation. Due to immense societal fears, vampiric characters are often portrayed as being reclusive. This alienation often manifests physically, as a large, secluded castle, or metaphorically, in the sense that the vampire typically only interacts with their intended victims. Considered as the progenitor of the vampire genre, John Willilam Polidori's The Vampyre

explores isolation and vampires by describing how the titular creature, Lord Ruthven, interacts with mortals. Ruthven prides himself on his cunning and finds great pleasure in torturing innocent humans. Ruthven particularly enjoys ruining the lives of virtuous women because dragging them down from the pinnacle of unsullied virtue

to the lowest abyss of infamy and degradation

brings him immense satisfaction (24). The vampire does this to countless adulteresses, but very few members of society catch on. These women are pushed out of their social circles and are forgotten. Despite this, the main character of the story, Aubrey, notices Ruthven's actions and becomes yet another one of the creature's victims. After too many harrowing encounters with the vampire, Aubrey finds himself unable to leave his room as his health declines. His sister shuns him and marries Lord Ruthven, while his servants stop attending to him. Upon Aubrey's death, it is revealed that his sister's sole purpose is to fulfill Ruthven's thirst for blood and amusement (45-50). Polidori portrays vampires as heartless creatures who simply enjoy toying with humans for the thrill of it. They enjoy watching people lose those they have always known. Despite their tendencies towards isolation, vampires are often ironically depicted as being the heart of social circles. Ironic situations are key in most vampire stories, as they appeal the main themes to the reader. Polidori sought to convey that things are not always as they seem, so he crafted Lord Ruthven as a seemingly noble character with a secret dark side. This tension between socialization and isolation helps fuel The Vampyre

and stories like it. Similarly to how irony is key in many vampire stories, the theme of duality is ever more prominent.

Whether it is a story of a vampire hunter and their prey or of immortality facing mortality, contrasts are ever-present in vampire tales. Carmilla, by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, explores this theme through the relationship between the story's vampire and her intended prey, Laura. Throughout their many encounters, Laura grows close to the beautiful Carmilla, but she describes herself as feeling a strange tumultuous excitement . . . mingled with a sense of fear and disgust

around the other girl (22). This mix of attraction and repulsion is a key theme of many such stories. The vampire sees their human partner as prey to be captured after a long hunt, wanting them to surrender to themselves fully to the vampire's overbearing will before they are devoured. Carmilla tell Laura that she live[s] in [Laura's] warm life, and [Laura] shall die – die, sweetly die – into [hers]

(21). Carmilla's use of shall

showcases how she feels in control of her relationship with Laura, becoming even more apparent when Carmilla declares that Laura belongs to her and always will (22). Such power dynamics are embedded into the genre, as also seen in The Vampyre

. Many of these stories use the titular creature to symbolize feelings like lust and desire. Laura's strange sense of excitement around Carmilla mirrors how many feel about giving into their temptations. Laura, an insert for the reader, sees that Carmilla's commanding personality is blindingly apparent, yet she cannot help but feel draw still to the vampire. The girls' relationship also demonstrates the contrast of immortality and mortality. Carmilla chases Laura across the boundaries of life and death. The two of them exist in different realms, and Carmilla knows the only way for them to be together is for Laura to die. This sort of chase evokes a sense of pathos from the reader, as two characters separated by fate is a common, yet tragic, trope. Carmilla asks Laura to trust [her] will all [her] loving spirit

, showcasing that Carmilla feels something for Laura, allowing the reader to sympathize with the situation (21). Some vampire stories aim to primarily elicit concern for the victim, while others prefer to pity the despondent vampire. Nevertheless, nearly every vampire story is riddled with pathos, especially the most successful tales.

Although vampire stories throughout history have different themes, they all contain a myriad of rhetorical devices that draw the reader into the narrative. The methods that enhance the story, most often symbolism and pathos, are those that reflect how contemporaries view vampires. Older vampire stories, notably those written in the 1800s, aimed to frighten their readers, perhaps best demonstrated by Bram Stoker's famed Dracula. While the story has a touch of the mysterious, the terrible, [and] the supernatural

, according to The Manchester Guardian, it mainly employs its blatant symbolism to scare the audience (1897). At the time, disease was considered just as frightening as Dracula himself. In the novel, Dracula's bite leaves a young woman named Lucy weak as water

and struggling to breathe, eventually succumbing to her mysterious illness and becoming a vampire (125). In Vampires, Burial, and Death, Paul Barber notes that vampirism occurs as an epidemic

, highlighting one major similarity between vampirism and disease (7). In this era, diseases were easily able to run rampant across Europe, especially in the countryside, which saw the most vampiric outbreaks. Little was known about what happened to the body postmortem, and even less was known about medicine. By Dracula's 1897 publishing, health regulations and vaccines were emerging, but the fear of illness persisted, as evident in the novel. Vampirism is treated as a condition contracted through bites, much like how any infectious disease is spread. This persisting fear of illness made it easy for Stoker to scare many with Lucy's symbolic illness.

In addition to rich symbolism, Stoker masterfully uses the plight of his characters to evoke a plethora of feelings from the reader. In Dracula, an English man named Johnathan Harker stays with the titular vampire, and he has one too many unsettling encounters with the Count to justify staying any longer. Harker desperately wants some sort of weapon to defend himself with, but he fears that no weapon wrought by man's hand would have any effect on [Dracula]

(68). Instead of simply being afraid, Harker expresses desire to protect his life, as he did not know what the vampire would do to him next. His fear seeps through the page to the reader, instilling a sense of dread for what is to come. The use of pathos abundant throughout Dracula is especially conveyed through detailed imagery. When Harker first enters Castle Dracula, the Count is described to have protuberant teeth

, pointed nails, and hands as cold as a corpse's (30-33). This depiction of the vampire allows the reader to place themselves before the creature, creating yet another gateway for Harker's unease to become the audience's. As opposed to simply describing a scary environment with unsettling characters, Stoker allows the reader to conclude their own reason for feeling frightened. Whether it was due to the characters' fear or societal fears, contemporary audiences was certainly afraid of Dracula. The ongoing success and effectiveness of Dracula, and many vampire stories like it, is largely due to the symbolism, pathos, and other rhetorical devices that keep the story relevant in showcasing human fears and desires.